- Home

- Piotr Barsony

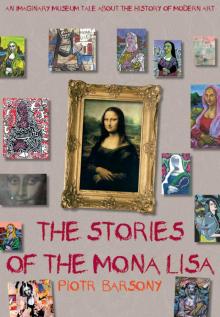

The Stories of the Mona Lisa

The Stories of the Mona Lisa Read online

THE STORIES OF

THE MONA LISA

For Maya Barsony,

and her cousins Roxanne, Shoshana, Héloïse, and Nora.

Based on an idea by Nadine Nieszawer.

Copyright © 2012 by Piotr Barsony

Originally published in France as Histories de Joconde © Hugo & Cie, 2010.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Sky Pony® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyponypress.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Manufactured in China, June 2012

This product conforms to CPSIA 2008

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barsony, Piotr, 1946- author, illustrator.

[Histories de Joconde. English]

The stories of the Mona Lisa : an imaginary museum tale about the history of modern art / Piotr Barsony ; translated from the French by Joanna Oseman.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-62087-228-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Painting, Modern--Juvenile literature. 2. Art movements--Juvenile literature. 3. Leonardo, da Vinci, 1452-1519. Mona Lisa--Juvenile literature. I. Oseman, Joanna, translator. II. Barsony, Piotr, 1946- Paris : Hugo & Cie, 2010. Histories de Joconde Translation of III. Title.

ND190.B2513 2012

759.06--dc23

2012015603

Artistic direction: Sandrine Granon and Stéphanie Aguado

Paintings: Piotr Barsony

THE STORIES OF

THE MONA LISA

AN IMAGINARY MUSEUM TALE ABOUT THE HISTORY OF MODERN ART

PIOTR BARSONY

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY JOANNA OSEMAN

“Dad, will you tell me a story?”

“A story?”

“Yes, any story you want.”

“Okay, sure. Why don’t I tell you a story about the history of painting?”

“Painting has its own story?”

“Of course it does. And the Mona Lisa, the most beautiful painting in the whole world, is going to guide us through it.”

“How come that’s the most beautiful painting in the world?”

“Nobody has ever been able to portray as much life in a face as Leonardo da Vinci did with the Mona Lisa. And life equals beauty.”

“It looks like a photo …”

“At the time, before photography had been invented, portraits had to be as accurate and realistic as possible. If I were to order a portrait of my daughter, for example, I would expect to see my daughter on the canvas.”

“So, when photos were invented, all the painters lost their jobs?”

“No, they just changed how they went about their work. The desire for paintings that looked like their subjects meant that accuracy and delicate shading and coloring were vital, but these requirements were suddenly no longer necessary. You could say that everything a photo did, the painters stopped doing by themselves.”

“So, what did they do?”

“That’s what I’m going to tell you about.”

“You can’t see this Mona Lisa very well. It’s just her reflection.”

“This is a painting by Claude Monet. It dates from 1875 and is called Impression, Sunrise.”

“I prefer the Leonardo da Vinci one.”

“That’s fine, but you’re going to have to learn how to look at things differently.”

“How?”

“You’ll see. Here, everything is just color and light. Monet didn’t worry about likeness, but rather about the impression of likeness. If you look again, the drawing seems to have vanished.”

“Ah-ha! That’s why he called it Impression, Sunrise!”

“Exactly. And this is the painting that gave its name to the great painting movement called Impressionism. The Impressionists’ first exhibition took place in the studio of a photographer named Nadar.”

“Weren’t they angry with the photographers?”

“No, the invention of photography was like a liberation for painters, an opportunity to explore new things.”

“Why did he give the same name to two of his paintings?”

“Look carefully, silly! It’s not the same artist. The other painting is by an Englishman named William Turner and was painted four years earlier.”

“So, Monet copied him?”

“Monet saw a Turner exhibition in London, and it obviously inspired him greatly. In fact, you could say that William Turner was the first of the Impressionists. And Impressionism is …?”

“Color and light.”

“Good job! The day that Monet died, one of his friends, Georges Clemenceau—who was also a French politician—cried out: ‘No black for Monet!’ Then he ripped down the colorful curtains that were in the bedroom where the body was resting and used them to cover his friend. So, as you see, ‘color and light’ is a philosophy that extends even beyond death.”

“She looks pretty against the blue sky!”

“This is Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh, a Dutch painter who lived in France.”

“It looks like it’s made up of waves …”

“Van Gogh put his troubles and torments onto the canvas.”

“Is that how he saw the Mona Lisa?”

“We see just as much with our hearts as we do with our eyes.”

“Why did he paint if he was so sad?”

“Because painting made him feel better and less anxious, took him away from his ‘black moments,’ as he used to say.”

“Ah-ha! He put suns in the sky to make everything better!”

“Without a doubt. He also painted sunflowers, plants that look like the sun and are always pointing towards its rays. The strange thing is that his self-portraits are done in the same reds and yellows as his sunflowers.”

“Did he want to be a sunflower?”

“I’m not sure he wanted to really be one. But just like them, he was always looking for the best possible light. That’s why he moved to Arles, which is a very sunny town in the south of France. He was obsessed with light, both exterior and interior. As a young man, he wanted to be a pastor so that he could preach about spiritual light to the men who worked overnight in the coal mines of Northern France.”

“Was he an Impressionist, like Monet?”

“At that time almost everyone was. The difference was that Monet painted what he could see, whereas Van Gogh painted what he felt inside. You could say that he was expressing his own impressions.”

“Wow, this Mona Lisa is beautiful! Such nice colors!”

“This is by Paul Gauguin. As you can see, Gauguin’s work is all about color. When he added some red, he would say, ‘This is the most beautiful red in the world.’”

“What about green?”

“The most beautiful green in the world, of course! This Mona Lisa was painted in Tahiti. She looks a bit like a statue, because Gaugin was strongly influenced by Polynesian sculpture. It was a way for him to escape the influences of the West.”

“He traveled a long way away to paint!”

“Because he could. The paint tube had just been invente

d, making it a lot easier for artists to travel. Before, they had too many materials to carry with them: paint pots, varnish, binders, fixatives, and so on. With a tube, everything is in the same place.”

“Did Gauguin like light too, like Van Gogh?”

“Of course. They were very good friends actually, but they used to fight a lot.”

“Well, that makes sense. One of them did flat paintings; the other used lots of waves.”

“They must have had very different personalities.”

“Were there other Impressionist painters?”

“Yes, a lot.”

“Why aren’t we going to look at them?”

“I can’t tell you about everything; it would take too long! We have to choose carefully. After that it’s up to you to find out whatever you want on your own.”

“This one is Paul Cézanne’s Mona Lisa. Now pay attention. This is going to be a tricky one.”

“It looks like the others to me, just with fewer colors.”

“Paul Cézanne was trying to resolve a problem. How do you get depth without the usual techniques of perspective, shading, and color tones? To get this depth, he decided to look at nature in terms of shapes and to put the colors next to each other without blending them together. Look at this Mona Lisa. The background is made up of little green squares and between them, there is a small space. The colors aren’t blended together like with Monet.”

“I think I understand …”

“To get a better sense of how he painted, you should go to your computer and look up his Mont Sainte-Victoire series. It will be much easier to see it there than on a portrait because there are lots of different planes.”

“Was he an Impressionist?”

“In the sense that he only used color, yes he was. But, unlike the others, he didn’t use it as a source of color vibration or of light. He used it for the composition and construction of his different planes.”

“It’s complicated!”

“I told you it would be; it’s unusual. You could say that Cézanne was a kind of researcher.”

“A researcher?”

“Yes, because he tried to apply a method and a theory to his work. That’s why it was so different and why it announced the arrival of modern painting. He used to say that painting was like thinking with your brush.”

“I understand it better now. Monet looked with his eyes, Van Gogh with his heart, and Cézanne with his mind.”

“I guess you could say that, yes.”

“This Mona Lisa is pretty. She’s covered in little dots!”

“This is a painting by Georges Seurat.”

“Did he have dots in his head, just like Van Gogh had waves in his?”

“In order to draw all these thousands of little dots you’d have to be a calmer person, not someone as tormented as Van Gogh, don’t you think?”

“But, then why did he draw all those dots?”

“He got this idea from Eugène Chevreul, a physician who discovered that two colors put side by side created a new shade between them that looks like a different, third color.”

“It’s not very easy to see that here!”

“You can only really see it on the big paintings, the ones in the museums. And anyway, it’s always better to see paintings in real life. But to get back to Seurat, he was trying to find a link between art and science.”

“Was he a researcher too, like Cézanne?”

“I suppose so, yes. He was a researcher, but the important thing for him was that his painting be beautiful. There’s another very nice Seurat painting that you must have seen before. It’s called A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. It shows people walking along the banks of the river Seine and a pretty lady under a parasol.”

“Now this one is a Fauvist Mona Lisa, which means wild.”

“You mean wild like a lion?”

“Yes, wild like a lion. During an exhibition, a French journalist thought that the colors used were too violent and gave this painting style the name ‘Fauve,’ which means ‘wild beast’ in French.”

“But it’s not that violent.”

“At the time it was. It doesn’t shock you because you’re used to bright colors. These days they’re everywhere. The most famous Fauvist painters are Henri Matisse and André Derain (1880–1954). Henri Matisse used to say, ‘When I use green, it doesn’t mean grass, and when I use blue, it doesn’t mean the sky.’”

“He sounds like Gauguin.”

“You’re right. Maybe Gauguin was really the first Fauvist. It was a movement that didn’t last very long though. Quite often, painters borrowed a name used by critics to make fun of them and united around it, using it to get more attention. As the saying goes, there’s strength in numbers.”

“I recognize this Mona Lisa. We have the same one at school, with the eye in the middle of her face!”

“So, you know who painted it?”

“Picasso!”

“Yes, Pablo Picasso, a Spanish painter who lived in France. And do you know why her eye is in the middle of her face?”

“No. “

“Look carefully at her face. Is it a frontal view or is it in profile?”

“In profile.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

“Are the eyes, nostrils, and mouth all in profile too?”

“Ah no! They’re facing us!”

“Picasso painted a profile that looks right at us at the same time. You could say he knew how to turn heads.”

“The landscape in the background is like Cézanne’s squares.”

“That’s right. When he was a young man, Picasso and his painter friend Georges Braque (1882–1963) went to a big exhibition of Cézanne’s work in Paris. When they came out they were extremely excited:

PICASSO: Well?

BRAQUE: It’s crazy how he paints his different planes.

PICASSO: We could do better than that though.

BRAQUE: You mean, show all sides at once?

PICASSO: Yes, as if you were walking around a cube.

BRAQUE: Shall we go to your workshop or mine?

PICASSO: Let’s go to mine!”

“Were you there, Dad?”

“No, I’m just imagining what they said. That’s how these two great painters, inspired by Cézanne’s work, tried to go one step further and show all sides of the image at once. Just as if they were turning a cube round and round, looking at each of its sides. That’s why they came to be known as Cubists. I could tell you a lot more about Picasso, one of the twentieth century’s greatest painters, but we have to move on …”

“Was he better than Leonardo da Vinci?”

“You can’t compare them, because they didn’t live in the same time period. But just like Leonardo da Vinci knew how to capture life in a face, Picasso knew how to capture it in bodies.”

“What is his most famous painting?”

“It’s called Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.”

“This one has a moustache! And why are there letters underneath it?”

“Read them out loud.”

“L … H … O … O … Q … I don’t understand!”

“It was the French artist Marcel Duchamp who drew the moustache on the Mona Lisa just after the 1914 war. If a French person read those letters like you just did, they would hear a rude word.”

“Why did he do that?”

“The First World War, which killed millions of people, had just finished. As a reaction to its barbarity, several artists formed an art movement that they called Dada.”

“That’s a baby word …”

“Exactly. They wanted to promote the spirit of childhood and mockery. If art and culture weren’t able to stop such horrific things, like war, from happening, then art and culture must be worthless. And if that is true, then all you can do is laugh.”

“And so they drew a moustache on the Mona Lisa?”

“Yes, and on culture and art as a whole. Duchamp wrote: ‘After al

l these millions of deaths, let’s invent the smile of tomorrow.’ He wasn’t officially part of the Dada movement, but he was with them in spirit. As you’ll see, he was like an artistic movement all on his own. He shook the art world by completely changing how we view creativity. Duchamp’s real name was Villon. Do you know why he chose to use this fake name, which was actually his mother’s name?”

“No.”

“Because in French, the expression ‘prendre du champ’ means to step backwards, to look elsewhere. He created a concept that he called ‘Readymade.’ For example, Duchamp took a stool and attached a bike wheel to it. That’s a Readymade.”

“So a Readymade is when you don’t actually ‘make’ anything at all?”

“You’ve got it! You don’t do anything—or perhaps just something small like adding a wheel to a stool.”

“But that’s not art!”

“Duchamp didn’t want to make art anymore. He hated the word ‘artist.’”

“Why? Why didn’t he want to be an artist?”

“It could have been because he was upset at the bad reception he got for one of his pieces, Nude Descending a Staircase. He must have thought to himself: ‘They’re all dumb. I’ll show them what art really is.’ To help you understand his thinking, I’ll tell you about one of his most famous Readymades. Duchamp exhibited an upside-down urinal that he called Fountain, signed by the manufacturer R. Mut and presented as a work of art. Think about those four phrases. It’s all back to front. The point is to make us think a little.”

“So, was that the end of art and painting?”

“No, painting can’t just disappear. It’s been part of our story since prehistoric times. But something else had been born now and art was no longer just something retinal.”

“What does retinal mean?”

The Stories of the Mona Lisa

The Stories of the Mona Lisa