- Home

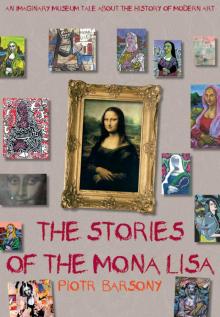

- Piotr Barsony

The Stories of the Mona Lisa Page 2

The Stories of the Mona Lisa Read online

Page 2

“The eye, the retina. Art became a matter of pure thought. No more expert skill or the craftsmanship of a painter’s work. From this point on, any artist following in Duchamp’s footsteps had to be very smart.”

“And funny too!”

“That’s not the Mona Lisa. It’s just some symbols.”

“It’s by the Russian painter Kazimir Malevich. He used geometric shapes to make up his pictures. In Russia, they were in the middle of a revolution. The revolution wanted to invent a new world and Malevich a new kind of painting.”

“Like Picasso, with the eye in the middle of the face?”

“No, not really. Picasso had created a new kind of representation of the world, but his models were still natural. There were still faces, bodies, landscapes. As for Malevich, he painted using geometric shapes: squares, triangles, rectangles, circles, and crosses. Signs that were invented by humans. It was his way of placing man at the center of creation. Malevich called this movement Suprematism.”

“Like God, the Supreme Being?”

“Yes, and just like God, he was all alone. He was pretty much the only member of his new movement.”

“He must have been kind of crazy.”

“You have to be a bit crazy to wander off the beaten track like that. The Russian Revolution was like a promise that finally anything was going to be possible. The artists at the time were very excited at that prospect. ‘Let’s just wipe the slate clean,’ said the Revolutionaries. So Malevich painted a white square on a black background, like an invisible door that made everything else disappear. An empty space on which to reinvent the world.”

“Duchamp drew a moustache on the Mona Lisa and Malevich made it disappear …”

“That’s it! Malevich, with his signs, had invented abstract painting. Painting that has nothing to do with reality, that isn’t imitating the world in any way. But his dream quickly became a nightmare as the revolutionaries turned into jailers. Malevich was imprisoned and tortured. After his release, he started painting again, but this time in a much more classical style.”

“Was he scared of going back to jail?”

“I’m sure he was.”

“Why did the revolutionaries turn out that way?”

“Because they wiped the slate clean.”

“But so did Malevich.”

“You can do anything you want with art, because it’s not reality. It’s like a dream, like the imagination. Anything can exist. But in real life, if you erase the past, history, culture, and everything else that makes up mankind, then you become a barbarian.”

“So, in art, you can do anything you want?”

“Yes, anything. But if art becomes reality, then it is no longer art.”

“This one’s just a scribble …”

“This is the work of another Russian painter, Wassily Kandinsky. You have to look at it in the same way you would listen to music.”

“You mean look with my ears?”

“Sort of, yes. This painter was very interested in harmony between colors and rhythms. Bit by bit, his scribbles become more structured, and he started to form geometric shapes. Look at the Mona Lisa herself. She is geometric, but the landscape behind is more scribbly. It makes sense to compare it to music. Kandinsky believed that there was a link between color and sound. Do you remember Seurat? He talked about colors as if they were vibrations. Sound is vibration. Maybe one day scientists will figure out how to bring sound and color together.”

“So, one day we could listen to Kandinsky’s music you mean?”

“Maybe one day, yes.”

“Did Malevich want to make music too?”

“No, Malevich mostly used black and white, whereas Kandinsky’s paintings were very colorful.”

“But is it also abstract painting?”

“Yes. The story goes that once Kandinsky found one of his paintings upside down in the corner of his studio, and he was struck at the harmony between the colors. The painting was of some Russian peasant women, wearing colorful dresses against a snowy background.”

“Are there other abstract painters?”

“Of course. There is one in particular that I know you will like; a Dutchman called Mondrian who inspired the French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent to create one of his dresses.”

“Is fashion art as well?”

“It is when it’s Yves Saint Laurent.”

“This one is scary.”

“This is an expressionist Mona Lisa by the German painter Otto Dix.”

“It makes me think of death.”

“The painting expresses what a lot of artists felt when confronted with the horrors of war—past and future—that surrounded them. One of the first expressionist works of art was The Scream by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1893). As he was crossing a bridge one evening, the sunset lit up the sky and everything looked as though it were drenched in blood. Munch began to tremble and felt as though an infinite scream were slicing through the entire universe. The Scream is the very definition of Expressionism.”

“I wouldn’t like to have that on my bedroom wall. I don’t think I could sleep.”

“It was made to keep you awake.”

“This one’s making a silly face. She must be an expressionist Mona Lisa too.”

“You’re starting to develop a good eye!”

“It’s easy. If she’s making a face or looks scary then it must be expressionist.”

“Yes, but Soutine didn’t paint violent scenes like the German Expressionists. He painted bouquets of flowers, landscapes, and ordinary people instead. There’s one kind of expressionism in the way you choose your subject and another in the way you put the painting on the canvas. Haïm Soutine, who painted this Mona Lisa, had a style that nobody in France had ever seen before.”

“Was he French?”

“No, he was Russian and was one of hundreds of other artists—from Poland, Romania, Hungary—who went to France to study art in Paris. Paris, with all of its museums and academies, was like a school for them. That’s why we call them the School of Paris painters.”

“It doesn’t look like Soutine learned much to me. It looks like he painted with his fingers!”

“You know, sometimes you have to look at a lot of different paintings by an artist to understand his or her world and to decide whether you like it or not. I bet that if you saw an exhibition dedicated to Soutine, you would come to like his work a lot.”

“He reminds me of Van Gogh. He uses waves in a similar way. But they go in all directions, as if there’s a storm. Did he have waves in his head too?”

“No, the waves in his work are a result of lessons he took as a child in Hebraic scripture, which is made up of little flecks, like baby waves.”

“What does that have to do with painting?”

“Handwriting is a person’s first initiation into drawing. If you learn to do something in childhood, you often tend to reproduce it later on. His artist friends from the School of Paris used waves in their paintings too. Do you know who went to his funeral? I’ll give you a hint: He was a famous painter.”

“Leonardo da Vinci?”

“Oh, come on!”

“Um … Picasso?”

“Yes, Picasso was there. He was so blown away by this primitive painting style, which was so full of life, that on that summer’s day in 1943, he decided to go pay one last tribute to Haïm Soutine.”

“Now here we are in Russia again. This is a constructivist Mona Lisa.”

“Like a construction worker? Is that why she was drawn with a ruler?”

“You’ve got it. The Constructivists distanced themselves from pure painting. They believed that art was meant to be applied to all fields. It was the Russian Revolution, and the new citizens needed engineers and architects more than they needed artistic painters. They needed machines more than canvases.”

“You’re right. This Mona Lisa does kind of look like a machine.”

“The person that founded this moveme

nt was called Vladimir Tatlin, a painter and sculptor who was interested in architecture. He designed a tower that was supposed to be a monument to the glory of the Russian Revolution, but at that time they hadn’t developed the right techniques to build it. It remained in the planning stage forever.”

“This Mona Lisa looks like a constructor.”

“Constructivist, not constructor! You’re right, though; this is the same movement as in Russia, only this time in Germany. This is Bauhaus, a German word that means ‘building house’ and that brings together all the different kinds of artists: craftsmen, engineers, architects, visual artists. The Bauhaus artists believed, just like the Constructivists, that art shouldn’t just be about creation, but should also serve society in some way: ‘The end goal of any visual activity is construction

… together we will create the construction of the future, which will embrace architecture, visual arts, and painting in one single form.’ Many of the objects and furniture that surround us today were created under this same influence. What we call design today was thought up by the Bauhaus artists. Bauhaus came to an end in 1933 though, when it was closed down once and for all under the Nazi oppression.”

“I like this Mona Lisa. She kind of looks like a dream!”

“This is a surrealist Mona Lisa. Surrealism was a follow-up to Dada, which was shooting off in all directions. The poet André Breton decided to organize this new movement by publishing a manifesto in 1924: Surrealism proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought in the absence of any control exercised by reason. He also inspired the dream analysis of the great psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud.”

“Did he want to paint dreams?”

“The dreams and subconscious thoughts that are buried deep inside us. The most famous painters of this movement were the Belgian artist René Magritte and, even more so, Salvador Dali, who was from Spain.”

“The one with the upturned moustache?”

“Yes, the one whose moustache pointed towards the sky. If you want, I can teach you a surrealist game. You get a piece of paper and write down any word that comes into your head. You fold the paper to hide what you have written. You pass the paper to your friend, who does the same thing and then passes it to someone else, and so on until it gets to the last person, who opens and reads it. This game is called ‘cadavre exquis,’ which literally means ‘exquisite corpse,’ because the first time the Surrealists played it the sentence read: The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine.”

“But what’s the point?”

“It’s a sentence that doesn’t bother with the laws of logic, just like dreams. It’s a free, surrealist poem.”

“You can see the landscape in the background through her face.”

“This is a Mona Lisa by Francis Picabia, an artist famous for his transparencies, just like you said. Here, the various planes are all jumbled together. I could have told you all about the history of painting, from the Impressionists to today, just by using Picabia’s work. He did everything.”

“Even Readymades?”

“Yes, even Readymades. He was a good friend of Duchamp, who he met in New York in 1915. They had lots of fun together. But whereas Duchamp lived quite a simple life, Picabia lived like a prince.”

“Was he rich?”

“Yes. It’s because of this—and his talent, too, of course—that he was able to be so productive.”

“Is money important?”

“It’s very important. I could also tell you the whole history of art through just his financial backers and art dealers. The Viennese writer Stefan Zweig said that nobody knew painting better than art dealers.”

“Why not?”

“When you bet your fortune on an unknown artist, it’s important that you don’t make a mistake. There is no such thing as a great painting movement without great art dealers. Paul Durand-Ruel for the Impressionists; Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler for the Cubists; Léo Castelli for Pop-art; and Charles Saatchi for today’s young English scene, one of the most creative current movements.”

“Did Leonardo da Vinci have financial backers?”

“No, he had people who commissioned work from him: the king, princes, the Church. In 2007, an English artist named Damien Hirst produced a piece that consisted of a laughing skull covered in 8,601 diamonds. He put it up for sale at $74 million and became the richest living artist in the world.”

“So, if something’s expensive, does that make it good?”

“These days there is a lot of confusion between market value and artistic value. Damien Hirst enjoys playing around with this confusion.”

“Has he earned a lot of money?”

“Oh yes!”

“Ew! This one’s ugly! Are we going to see some nice ones again soon?”

“But this one is nice! It’s a Mona Lisa by Francis Bacon, an Irish painter who was a big fan of Picasso. But whereas Picasso shows the exuberance of life, Francis Bacon’s work is violent and dark.”

“If he was inspired by Picasso, why did he draw such sad pictures?”

“We paint what we are. Bacon didn’t paint violent scenes in the same way the Expressionists did, but he expressed his own violence through his painting style.”

“What about the lines all over the face?”

“They are mostly curves that he used to distort the face without it becoming just one big smudge. He often displayed his subjects in geometric frames, like transparent prisons in which the bodies were held captive. He was actually expressing his own feelings of oppression and suffering.”

“It looks like he paints with his fingers, like Soutine.”

“His fingers, his brush, and also tubes of paint, which he would crush against the canvas. It’s almost as if Bacon painted with a knife or a scalpel. The face of this Mona Lisa looks as though the flesh has been cut out, like a stencil. He always liked to quote this line by the poet Aeschylus: ‘The smell of blood is always with me.’”

“I never want to go see a Francis Bacon exhibition.”

“Maybe when you’re older. Bacon wasn’t trying to create horror, just paint it. Right down to its most visceral representations. As if he were pulling out people’s hearts to grab hold of life itself.”

“Was he a serial killer?”

“No, he must have been a very good man, but he suffered a lot on the inside. You can see that just by looking at his paintings. That’s what they embody.”

“What does ‘embody’ mean?”

“It means using the body to show life. Leonardo da Vinci, Van Gogh, Picasso, Soutine, Bacon—they were all trying to do that in their work. It’s the hardest part, but when you get it right, it becomes something universal and timeless.”

“Like the Mona Lisa’s smile?”

“Exactly, like the Mona Lisa’s smile. It’s what every painting aims to do. Painters have a different way of looking at things, but they’re all looking for beauty. They see it where others don’t. For them, good taste and bad taste are barriers that don’t exist.”

America

after 1945

“I feel like I’ve seen this Mona Lisa before.”

“This one is by Willem de Kooning, another painter who admired Picasso.”

“They all admired Picasso.”

“That’s because he was the best.”

“This one looks kind of scribbled. She’s scary too—a bit like the expressionist paintings.”

“You’re really learning how to look now. But instead of saying ‘scribbled,’ what’s the more technical word that would fit here?”

“Abstract.”

“Exactly. This movement became known as Abstract Expressionism.”

“That was easy!”

“Let’s leave France now and fly to the United States.”

“The United States?”

“Yes, to 1945, the end of the Second World War. The Americans were victorious and the country was young and powerful. A lot of artis

ts fled a devastated Europe and took refuge in New York: Duchamp, Picabia, Breton, and so forth. This mix of a young and dynamic country with the European avant-garde quickly turned the city into the art capital of the world.”

“Paris wasn’t the center anymore?”

“No, that part was over for Paris. In New York, everything was big: the city, the studios, the apartments. The painters could produce huge canvases. They would set them up in front of them or even lay them on the floor. No more stools and easels! Now they could actually stand in front of their work. This is what was called Action Painting. Gigantism was the primary characteristic of American painting.”

“This one looks like someone dropped paint on the canvas.”

“This is a Jackson Pollock Mona Lisa. He would lay his canvas out on the floor and paint from above. He threw paint by flicking a stick that he had dipped in different colored pots.”

“Was he the first person to paint on the floor like that?”

“Not the first. He was copying the Native Americans, who painted magic on the ground using colored sand in order to communicate with the spirits of their elders, who were thought to be underground. Magic is an ancestor of religion. In our culture, religious painting looks to the sky, the place we imagine God to be. To look at frescos or stained glass you have to look up. When Pollock showed his work in a gallery, it was as if he was turning the room upside down, making the floor and walls switch places.”

“Did he paint magic on the walls?”

“He tried. But he wasn’t a shaman.”

“What’s a shaman?”

“A bit like a witch. Art hasn’t always meant the same thing at different periods and for different civilizations. What we understand today by the word ‘artist’ is a recent, Western creation.”

The Stories of the Mona Lisa

The Stories of the Mona Lisa